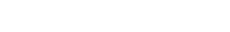

BREITKOPF & HARTEL - 15131

Bach 15 3 Part Inventions for String Trio

Composer: Johann Sebastian Bach

Publisher: Breitkopf & Härtel

Instrumentation: Mixed

Format: Chamber Parts

Binding: Stapled

Dimensions: 9 in x 12 in

Pages: 72

Bach 15 3 Part Inventions for String Trio

Juilliard Store

144 West 66th Street

New York NY 10023

United States

Choose options

Bach 15 3 Part Inventions for String Trio

Juilliard Store

144 West 66th Street

New York NY 10023

United States

Bach 15 3 Part Inventions for String Trio

Juilliard Store

144 West 66th Street

New York NY 10023

United States

To obtain new chamber music by Johann Sebastian Bach, one can either go back to the roots, to the original version, or one can move on creatively... This is the path that Mozart took by forming string trios from pieces by Bach. Wolfgang Link picks up this great tradition in his arrangement. While not every three-part harpsichord piece is suitable for a string trio arrangement, the 15 Inventions BWV 787 to 801 seem tailor-made for this. The range of the voices perfectly fits the classical scoring, and Bach himself would no doubt be satisfied with the completely new sound. He would probably remember that he himself provided the initial spark for their instrumental scoring when he called the three-part inventions "sinfonias."

Preface:

This arrangement of the three-part inventions – Bach himself called them “sinfonias” – is dedicated to all the admirers of the St. Thomas cantor who consider it a regrettable omission that he wrote far too little chamber music for several stringed instruments.

Baron van Swieten, who loved and promoted the music of Bach, encouraged no less a composer than Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to select appropriate pieces from Bach’s vast keyboard oeuvre and make them playable for strings. This string-trio adaptation of the three-part inventions thus follows a noble tradition.

Johann Sebastian Bach no doubt had a completely different purpose in mind when he created these keyboard pieces. Theywere, and still are, considered excellent practice pieces for the budding keyboard virtuoso. The aim of this edition, however, is to give to three stringed instruments polyphonic music from Bach’s pen so that they may “regale” themselves with musical delicacies, as one might have said in the Baroque era.

The particular charm exuded by this music results precisely from the combination of different stringed instruments. For one, the voices can be distinguished clearly, which is obviously not the case with a harpsichord or piano; sustained notes fade away on the keyboard, but not on a string instrument. The different tone colors of the various instruments also provide a distinct and highly original note here as well.

Bach’s three-part inventions actually seem tailormade for string trio. There is only one single note among all the voices in these pieces which exceeds the tonal range of one of the instruments. This is why a slight alteration had to be made at the close of the Sinfonia 6 so that the figure could be maintained. This close is offered in two versions, whereby the figure is played in the first by the violin and in the second by the viola and violoncello; the descending figure as well as the ascending fourth at the end remain unchanged.

Sinfonia 14 also offers two different endings: in one we have a crossing of the parts, in the other the violin and viola remain in their respective registers, determined solely by pitch.

Sinfonia 15 is offered in two versions here. This concerns measure 28, where, diverging from the original voice leading, the high register in the cello is taken over by the viola. The phrasing and articulation slurs are to be understood as a suggestion.

The notation was adapted to current usage. Tempi, dynamics, phrasing and ornaments correspond to the original musical text and – inasmuch as they were not supplied by Bach himself – are left up to the performers and their sense of style.

St. Ingbert, Fall 2007